Skiing the Fuhrer Finger

“Ah Japhy you taught me the final lesson of them all, you can’t fall off a mountain.”

Note: Throughout this I’ll use the native names of the Washington volcanoes. Namely, Tahoma instead of Rainier, Pahto instead of Mt. Adams, Wy’East instead of Hood, and Loowit instead of St. Helens.

I first summited Tahoma in the summer of 2021. We slogged our way up the Emmons glacier, touched the crater in gale force winds, and slogged our way back down. I never came out of the middle of the rope team for the 12 hours between leaving camp and returning, and I was not a happy camper by the descent.

Grumpy during my Emmons descent

So I resolved that I would return to summit it in style. A route that did not require as much time on a rope team, had minimal walking in darkness on a glacier, and where we could make our way down on skis instead of foot. I planned to do so with Brent, a frequent victim of my big ski mountaineering plans. After a long search for a third party member, we convinced Adam (with whom I had skied Pahto) and set out to ski the “Fuhrer Finger” on May 11th.

Brent's gear that he had to fit in his backpack

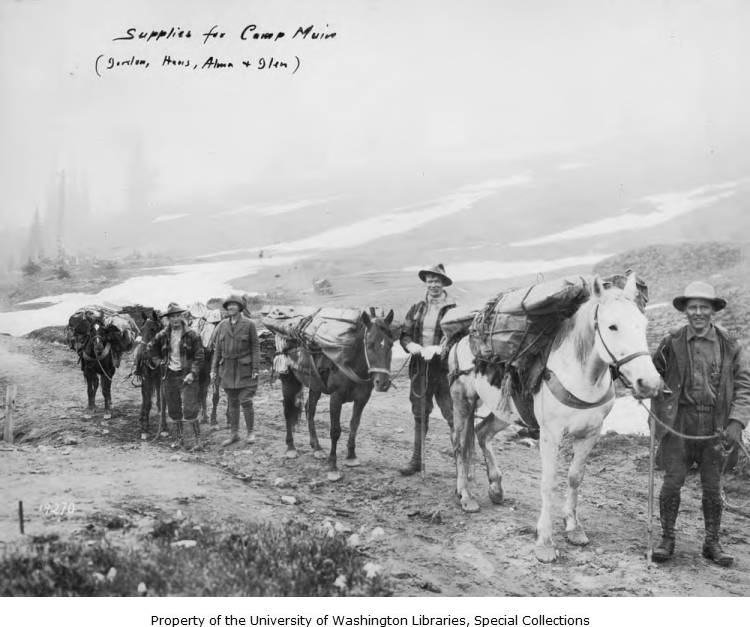

The route is named after Hans Fuhrer, a Swiss mountain guide who organized the first expedition up the line on July 2nd, 1920. They climbed it in one push, bringing “substantial food for a day–for [they] all believed in eating heartily on a climb”. The main feature of the route, known as the “Finger”, is a steep chute climbing out of the Wilson Glacier and connecting to the Upper Nisqually. The Fuhrer party described it: “For a half-mile at about 9,500’, we left the glacier route for the first time. A break in the rocks led us to a steep, isolated snow finger, part of the route we had examined for a year through the telescope. While extreme in steepness, this slope did not avalanche and it flattened below to a safe snow field. It connected us nicely with the more flattened shoulder of the mountain at 11,000 feet altitude.” (Quotes from the Fuhrer trip report).

We didn't get to use any mules!

It would be difficult to write a more appealing description of a big mountain ski line than steep, low avalanche risk, and flattening out to a snowfield at the bottom. And indeed, this is now considered the most classic ski line on Tahoma, particularly if conditions are such that you can ski from the summit to the Nisqually Bridge, a 10,000 foot descent - often called the longest ski run in the contiguous US.

We are not as tough as Hans Fuhrer, so we set off on Thursday afternoon with the intent of spending an evening at 9,500’ and setting off for the summit early the next morning. The lower route has changed substantially since the original climb, as the lower glacier has receded and gone through several outburst floods. But the gist of it remains, and we set out from Paradise with heavily loaded packs. We descended into the valley that holds the Lower Nisqually and crossed the glacier. We ascended the other side towards a ridge line and followed the ridge up to “Castle Rock” at 9,500’.

Adam making his way up the ridgeline

There we found a snow-free bivy site that we could squeeze ourselves into. Camp was spectacular - a beautiful evening with views of Wy’East, Pahto, and Loowit. The Fuhrer party also saw the “immense panoramas of the ‘Guardians of the Columbia’”, although they saw a Loowit with the top still intact. The evening was spent with the usual high camp activities - prepping climbing gear and melting snow, and then we settled into bed around 8pm.

The next six hours were spent trying to catch whatever sleep we could while sliding into each other on the sloped bivy site. I was certainly wishing Hans’ dream of “a shelter cabin at 9,000 feet” had come true. “Thank God it’s over” Brent said when his alarm went off at 2 am - despite the awful hour we were all happy to get out of our sleeping bags and start packing up. We had some delays due to the standard litany of gear problems (and I managed to very proudly poop at 2:30 am), but by 3am we were roped up and walking out of camp across the Wilson Glacier towards the Finger.

Adam and Brent in the lower section of the Finger

The Wilson crossing went smoothly despite much of the path being covered in fairly fresh avy debris, and by 4 am we were unroped and picking our way up the Finger. Ski mountaineers don’t enjoy walking, as a general rule, and French stepping your way up a 1,500 foot couloir is a particularly unenjoyable form of walking. Adam in particular is more of a skier and found the unprotected steep booting a bit heady. But the snow wasn’t too firm, and the exposure was minimal, and by the time the sun was rising we were at the top of the chute.

Nothing brings out smiles like the sun

We had a quick break to watch the sunrise and have some snacks, and then we continued to push on the final 500’ towards the Upper Nisqually. This was the most broken up section of glacier that we had to navigate, and a mountain guide we had interrogated for beta had told us that it “was as complicated as always”. However there was a skin track to follow and the snow was still fairly firm even as the first rays of sun reached the surface, so I felt confident it would not be problematic. As we approached the first crevasse we got back on the rope and continued walking.

Climbing the Upper Nisqually

Brent, however, had started feeling really awful. I was surprised, this had been a relatively light day compared to past trips we had done together. Adam and I gave him the standard words of encouragement and we slowed our pace down quite a bit. But by the time we were in the meat of the glacier at 12,500’, Brent could only walk a hundred yards without stopping.

We took a long break at a nice spot to sit and chatted with another party that had been climbing behind us for the past couple hours. After about 20 minutes, we decided to give it another go and started walking again. Within 5 minutes, Brent’s heart was beating so hard that it hurt, and he felt lightheaded. At that point we decided to turn back, it didn’t seem safe to keep going up higher given the symptoms he was describing. We returned to our nesting spot and spent about an hour waiting for the snow to soften so that the skiing would be better. Adam and I practiced juggling snowballs and drank the beer that we had carried up for the summit. Brent practiced not vomiting.

Two very different experiences on the same sunny morning

Ironically, while the Finger is now known primarily as a route that is climbed for the sake of the descent, the original Fuhrer party went down by the “Gibraltar” route. The route was not skied until 1980. Well in one hour, we skipped 60 years of mountaineering history and at 10am we put our boots in ski mode, tightened our helmet straps, and swallowed the inevitable fear of the first turns on high consequence terrain. I was nervous about Brent since he was not his usual self and this was, while easy, unforgiving skiing. But once the first couple turns were behind us we settled in and enjoyed the perfect corn and amazing views.

Adam and Brent getting their first turns with cratered Loowit in the background

Very quickly we were at the top of the Finger. We dropped in and it was as perfect as we could have hoped for. Besides some fields of avy debris, it was good to great corn and very solid. We didn’t trigger any sluff and enjoyed skiing the picturesque and epic feeling couloir.

Living a dream!

Eventually we arrived at the bottom of the chute, legs on fire from the steep turns, and roped up to cross the Wilson again. It was in much different condition at eleven am than three am, and Adam even partially collapsed a small snowbridge! A good reminder that even though we were out of the steepest terrain, we were still in an active glacier and subject to all the dangers that brings with it. Luckily the crossing didn’t have any further incident and we arrived back at camp around 11:15.

"Do you feel safe?" "Yeah!" "OK let me take a pic real quick"

We packed up as quickly as we could, although a marmot had gotten into some of our trash (including, disgustingly, my blue bag) and began descending towards the bridge. It was hard to believe that we still had 5,000’ of descending ahead of us! Unfortunately the day had continued to be hot and the snow low down was quickly turning into the slush that any spring skier in the PNW is familiar with. Combined with the sudden expansion of our packs, we were very excited to be down at the bridge.

Picking our way down the river

We dropped down from the ridge onto the Lower Nisqually. We triggered some medium sized wet loose slides on the steep valley walls which made us even more excited to be out of the snow. Luckily the actual glacier itself was not as steep, and we zipped down towards the start of the river. We spent the next 30 minutes picking our way between rocks and over snowbridges, and finally made it to the Nisqually Bridge on our skis! I committed to actual making it under the bridge and did some log acrobatics with my skis on.

Proof that I made it to under the bridge

And then we did our final ascent - 50 ft up to the road - and I hitched a ride back to my car with a nice family from Ohio. Overall an excellent trip and a good reminder that “it's the sides of the mountain which sustain life [and ski turns], not the top.”

Recreation of the hitching - it was too fast to get a real pic!

Climb Timeline:

- 3 am departure from Castle Rock camp.

- ~5:30 am top out on the Finger.

- 6:30 am roped up on the Upper Nisqually

- 10 am began descent from 12,500’

- 10:30 am entered top of the couloir